Sitting down for a conversation with award-winning author, poet, journalist and teacher, Maree Giles.

Maree Giles was born in Penrith, NSW, Australia. In 1970, when she was sixteen, Maree was committed to the notorious Paramatta Girls Home in Sydney, an event which changed her life.

Q: Maree, You’ve had a long career as a writer – as a journalist, novelist, teacher of writer. Where did the motivation to write come from?

My grandmother and my mother, who brought me up, encouraged me to read. From a young age it was a natural progression to writing stories and poetry.

I was also lucky to have had two excellent English teachers who encouraged me. The first was at St Catherine’s Girls’ School in Sydney, where I was a boarder. The second was at Narrabeen High School. As an only child I was very much a loner, so I turned to reading for company. When you spend a lot of time alone you develop a good imagination.

When I was sent to Parramatta Girls’ Home (PGH) at the age of sixteen, I was allowed to attend school. Not all the girls in the home went to school. Most worked in the industrial laundry that serviced the asylum and men’s prison next door.

School at Parramatta Girls’ Home consisted of one classroom and one teacher, a stern Scotswoman called Mrs McGrath. She mentored me through the Nurse’s Entrance Exam. It wasn’t my choice to study nursing. The authorities and my mother thought it was a good idea. At that stage I still had no idea what I wanted to do with my life.

At Parramatta I was the librarian. The library became my sanctuary. I read every book, sometimes twice. Every book spoke to me of freedom. One book in particular had a big influence on me: A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens. In the school room I wrote poetry about what it was like inside PGH. I gave some of my poems to another girl. An officer confiscated them and tore them up in my face. She admitted they were an accurate, well-written portrayal of life as a Parramatta girl. But writing about it was strictly forbidden. The staff didn’t want the truth leaked about their brutality.

When I was released from PGH I was hounded out of Australia by the police constable who originally arrested me. She doggedly wanted to have me sent back to PGH for the smallest misdemeanour, for example, staying out too late at night. I did not want to join the long, depressing list of recidivists at PGH. I was determined to never go back. So, my mother bought me a plane ticket to Wellington, New Zealand. I was only seventeen.

At first, I lived at the YMCA. I found a job with the Inland Revenue as a clerk. Then I decided to make use of my nursing qualification, and enrolled as a psychiatric nurse trainee, at Porirua Hospital. But it was a heartless place. I felt I had left one violent institution for another. After 12 months, and many fruitless attempts to convince my superiors their staff were bullies, I quit.

In 1972 I studied journalism at Massey University. I knew from the outset I had found the right career and have been writing professionally ever since.

Q: You have fictionalised your story in Invisible Thread (2001), which as you say, “was written ahead of its time“, ie, before nation-shocking inquiries about the treatment of children in orphanages, children’s homes, detention centres, and foster care. Can you tell us what motivated you to write about your ‘care’ experience and why you chose to write your story as fiction instead of writing a memoir?

I wanted to expose the bullies and sadists (staff and some inmates) who took advantage of the young girls incarcerated at Parramatta. I can’t think of my experience there as having been in “care.” There was no “care.” PGH was the most notorious and violent of all the homes in Australia at that time.

I thought no one would be interested in my story. And I was afraid of any repercussions. This led to my decision to write it as a work of fiction and change all the names. I thought the public’s perception would be that I had deserved to be sent there because I was a “bad girl.” I renamed the home Gunyah, which is an Aboriginal word for shelter. I chose it for its irony. There was no shelter in Parramatta Girls’ Home. It was a place where young lives were systematically and routinely damaged and broken.

During my time inside PGH I became friends with a girl I will call “Hannah.” Her new-born baby was taken from her illegally at the Crown Street Women’s Hospital. The baby was adopted out. “Hannah” never saw her baby again. It left her heartbroken. She ended up in Silverwater Prison for possessing heroin. And that is where, in total misery, she ended her own life by hanging. I felt that her tragic story was worth telling. It struck me as the right fit for the book. “Hannah” was not the first girl to have her baby forcibly removed by the authorities for the thriving adoption market. The lifelong mental anguish these young mothers have suffered is immeasurable.

I didn’t know when I wrote the book that it highlighted two historic events that would later become the focus of two separate Public Apologies in Parliament. Again, this is why I describe it as being written “before its time.”

I have always hoped that my book would validate these experiences and events and bring some small comfort to all the girls who suffered. And I hoped that the book and publicity about it would alert anyone working with young people in care to juvenile vulnerability. A large institution sheltering children is an easy environment for bullying to thrive. Percy Mayhew, for example, who was the superintendent at PGH when I was there, groomed his officers to take advantage of this secret setting to abuse the girls. No one would ever take the word of a Parramatta Girl against an officer of the Child Welfare Department.

Q: Even today people who’ve been in state ‘care’ can feel stigmatised and marginalised simply because they’ve lived away from their families. Was that your experience and if so, were you aware of the long history of stigma when you were writing Invisible Thread?

Yes, I was aware of the long history of stigma and marginalisation. PGH had a bad name. Although I had never met any girls who had been to PGH before I was detained, I believed if you were sent there you must have done something very wrong, you must have been a “bad person,” a “bad girl.”

The stigma also motivated me to write about it and to try and prove that what took place there was wrong. But there was still this overriding sense that it was me who had been deviant, and that I somehow deserved to be punished and humiliated.

According to Wikipedia, Parramatta Girls Home served the dual purpose of both a reformatory and training school, with girls committed to the institution on “complaints” under the Child Welfare Act 1939 (NSW) as “delinquent” — uncontrollable, absconding from proper custody, breached probation; “neglected” — exposed to moral danger, no fixed place of abode and destitute, improper guardianship, truant; or “offences juvenile offenders, Crimes Act” — stealing, assaults, robbery, murder, sex offences, malicious damage.

If you did not know the truth, you might assume from the above extract that the home was full of rough girls who were basically petty criminals. Parramatta Girls’ Home was a place where violence flourished freely. The staff were not properly trained to care for and help these young innocent girls in a supportive way.

Until I wrote Invisible Thread/Girl 43, I had tried to put PGH behind me and rarely spoke of it. Yet the experience has affected my whole life. The trauma of being a Parramatta girl runs deep. It was hard to accept that I had been sent there, because I came from a good family. Although I grew up without my father, my mother and grandmother were respectable, hard-working, caring women. They provided me with a decent, loving home under difficult circumstances.

Q: You’ve chosen to take up other aspects of Australia’s history that many members of the community would prefer we forget. What motivated you to write Under the Green Moon (2002) and The Past is a Secret Country (2006)?

Parramatta Girls’ Home had revealed injustice and prejudice that I had until then not been aware of. There were several indigenous girls at Parramatta. I began to think more and more about their lives, and much later when the government apologised to the Stolen Generations, I became deeply interested in their culture. When I was growing up in Garigal country around Narrabeen Lagoon I often came across evidence of indigenous people. Years later, when I learned about the Stolen Generations, I felt a strange affinity with their trauma that came from being separated from my mother and locked up. My mother was also a huge inspiration behind the novel. She had a fascinating childhood and life in Botany Bay, not far from the La Perouse Aboriginal community. And my great grandparents, Rachel and Clarence Calthorpe, who did in fact drown in a shipwreck off Cape York en route to visit family in England, were another big inspiration. These were some of the things that moved me to write Under the Green Moon.

The Past is a Secret Country was inspired by my half-sister, and her half-sister. We didn’t meet until I was in my thirties. I thought it would be interesting to write about three Aboriginal sisters born to a white mother and put up for adoption in Melbourne by their father, a bigoted farmer in the Snowy Mountain region. I can’t give too much away about the story, but it is a confronting book, and that was my intention.

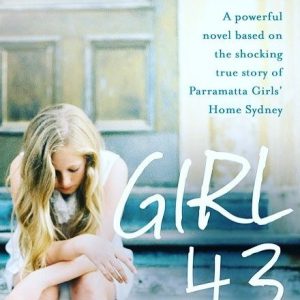

Q: Invisible Thread was republished as Girl 43 in London in 2014. Can you tell us about the differences in the reception of the novel given the republication in a different time and place?

By the time Girl 43 came out in 2014 there had been a lot of publicity about what had happened at PGH and the Hay Girls Home. There was a Royal Commission into Institutional Sexual Abuse. And the Redress scheme.

And two Public Apologies by two different Prime Ministers: Kevin Rudd to the Forgotten Australians and former child migrants (children in care) and Julia Gillard to victims of forced adoption. Then came Alana Valentine’s play, Parramatta Girls.

Girl 43 did not get the marketing boost it deserved. And when you say people would “prefer to forget Australia’s dark history,” that is a reason why it didn’t make it onto the bestseller lists.

Invisible Thread was optioned by three major film production companies: Elton John’s Rocket Pictures; David Hannay Productions; and Aquarius Productions. The story is an important historical record. Its reach is enormous. When you consider that there were more than 800 care homes across Australia in 1970 when I was incarcerated, that is a staggering statistic. Why were so many children let down? What is wrong with our society that allowed this to happen?

Invisible Thread/Girl 43, is an important story with big, scary themes.

Q: Have you read Charlotte Wood’s award-winning The Natural Way of Things (2016) which is partly based on the Hay Girls’ Home, and if so what do you think of it?

Yes. When it was published, I had mixed emotions, because it felt so familiar. But there was also a sense of satisfaction and validation. It is a fiercely feminist book and unashamedly anti-patriarchal. It is true that the highest principle available to a Parramatta or Hay girl was self-preservation. I am sure the same could be said of anyone in the care system.

When you have written a book from your own experience and drawn on the experience of people you have known, and you read someone’s speculative interpretation of that experience, it feels invasive and imbalanced. I know her intention was to throw a powerful light on misogyny, and she achieved that. So, it is a real victory for women. But I cannot emphasise enough that my experience inside Parramatta was not only one that involved violent men. The majority of female officers were abusive and so were some of the girls. This is a truth that is very uncomfortable to hear. I think that is what shocked me as much as the male abusers. That women and girls my age could be violent.

Invisible Thread/Girl 43 is based on the truth behind some of the most shameful and violent events in Australian history. I have campaigned and advocated for Girl 43 to be listed on the secondary school’s Australian history curriculum as Recommended Reading. My publisher and I sent out hundreds of copies to schools and universities. Anyone studying social work, Australian history, and nursing, should read it.

I think there is still widespread ignorance in Australia about these tragic events. A lot of people don’t want to hear about it. I have lost track of the number of times someone has told me to “get over it.” You don’t “get over” a human rights violation, and nor should you be expected to. That is a form of insidious victim shaming and gaslighting. The fight for better education on these issues should never stop.

Q: What are you currently working on?

A novel set just after the second world war in Sydney, a time of huge optimism and excitement. A collection of short stories, essays and poems about my life, and a poetry collection devoted to the history of and experience inside Parramatta Girls’ Home and the Hay Institution.

Q: Are there other stories since Invisible Thread you would recommend to readers as providing insight into the experiences of Australians who identify as Care Experienced or Care Leavers?

- Empty Cradles by Margaret Humphreys

- Orphans of the Living: Growing Up in ‘Care’ in Twentieth-century Australia by Joanna Penglase.

- The Parramatta Female Factory Precinct website which has a wealth of information: https://www.parragirls.org.au

- The Forgotten Children by David Hill

- Coram Boy by Jamila Gavin

- CLAN – Lifelong Support for Care Leavers in Australia and New Zealand : https://clan.org.au There is a long list of links to research papers on care leavers on the CLAN website: https://clan.org.au/resources/research/

- Also Resources for Teachers and Students on my website.

Q: What advice would you give young people leaving the state care system today?

Being in the “care” of the state makes you wonder what you have done to deserve it. You constantly ask yourself why? Am I really a “bad” person? Am I unwanted? Am I not good enough for my parents? Why have I been abandoned? Why have I been locked up? These questions can haunt and traumatise. I think I would say: Don’t blame yourself. It’s not your fault. And I would go on saying it so that it becomes their mantra.

A child’s vulnerability when in “care” is the most important reason to fight for better protection and education.

I found it ironic that I was charged with being “exposed to moral danger” and sent to a violent institution where I was exposed to far worse than living with my boyfriend.

Yes, at sixteen I was too young, naïve, and gullible, and he took advantage of me. And I stupidly thought it was all “love.” But I was never physically or mentally harmed by him. And let’s not forget that I was over the age of consent. I regret making Ellen, the main character in the book, fourteen. It would have been far more shocking to make her over the age of consent – sixteen – to highlight the hypocrisy of the flawed system for charging her with being “exposed to moral danger” and locking her up for it. How could a girl of sixteen be charged, but not the boy who was involved? My boyfriend knew he was safe from any criminal charges. He even came to the police station where I was being held to ask if he was wanted for questioning. They said: No, you are free to go. No questions asked. Suddenly I was a ‘criminal.’ Having my fingerprints taken, being transported to the Children’s Court in handcuffs and a police car with tinted windows. Then told by the magistrate I was ‘uncontrollable’ and ‘exposed to moral danger’ and had to be sentenced to the scariest place in Australia. It was about being taught a lesson by state-employed thugs. The excuse they used for locking us up was to ‘protect us.’

Care Experienced people: Make sure when you start your own family that you have the support and resources you need to do the best job you can as a parent. Believe in yourself. In the end, we only have ourselves to truly rely on. Make healthy choices that will build your confidence and equip you well for the challenge of living a productive, creative life. Education is so important. Get one. Go to school and college, and university. Or learn a trade. Earn your own living and try not to rely on the state to prop you up. Money is vital for helping you feel independent and confident. That’s not greedy or materialistic, it is about being practical and self-reliant.

The world is unpredictable, but the one thing you can control is your self-belief.