This year, I came to Edinburgh to do some research at the National Records of Scotland. Like thousands of other people, I arrived at Waverley station.

On my day off, I walked through the city to spend an hour or two at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, housed in a beautiful and imposing early nineteenth-century building on a hill above Dean Village. I did all these things, without knowing that I was walking on the two sites of the first national home for orphaned children in Scotland – the Orphan Hospital. Millions of people pass through Waverley station and thousands wander the galleries of ‘Modern Two’ without knowing the history of these places.

In 1733 a group of Edinburgh merchants and the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge hired a house in Bailie Fyfe’s Close, under the present-day North Bridge, to house 30 children. A commemorative pamphlet published for the Hospital’s anniversary in 1833 reported that the founders were moved to act by ‘the number of orphan children in Edinburgh and other parts of Scotland, who were left in very destitute circumstances, and exposed to all the evils inseparable from a state of idleness and ignorance’. The foundation of the Hospital was part of a wave of philanthropic initiatives across Europe in this period, prompted by growing beliefs that children required special care and attention separate to adult charities, and that the increasingly affluent middle-classes should use their new wealth for charitable causes to demonstrate their virtue and piety. A home for the most deserving of Scotland’s poor – orphaned children – was an ideal cause for Edinburgh’s merchant elites.

The Hospital was not large; at its height it housed only 200 children, brought from across Scotland. Admission was difficult. It was theoretically open to any child who could demonstrate that they had no one to care for them. Petitions for admission survive in the National Records of Scotland from the families of children who had lost one or both parents, who had been living with grandparents, aunts, uncles or siblings who could no longer care for them because of their own old age or ill health, or children from large families who were simply too poor to care for so many siblings.

In practice, though, the governors placed strict limits on admission because they did not have enough money to take all those who applied. Children had to be aged between 7 and 11 years old, and petitions asking for admission had to be signed by their parish minister and elders, to testify to their moral character and the truthfulness of their account. Their parents had to have been married; illegitimate children were not included in the governors’ understanding of a deserving object of charity. If their petition was satisfactory, the child was then summoned to Edinburgh to be interviewed by the governors and to undergo a medical examination, to check that they carried no infectious diseases that could endanger other children in the Hospital, and that they were fit to work. On the backs of the successful petitions, in which families poured out the circumstances of their poverty and inability to care for their children, the governors wrote the words ‘a proper object of pity’.

Right from the beginning the Hospital was motivated by religious ideals which connected hard work, good citizenship and Christian piety. Its aims were to take children whose parents could no longer care for them and provide them with food, clothing and shelter, but also a basic education and training in linen and woollen manufacturing (for the boys) and housework (for the girls). This trained children in the habits of morally-improving hard work, and prepared them for future life in apprenticeship and domestic service. The author of the 1833 Historical Account of the Hospital congratulated its governors on their success ‘in the rearing and establishing creditably and usefully in the world a great number of children who might otherwise have become the prey of idleness, misery, and vice, and, as the chief means of securing that end, of early instilling into their minds the principles of religion.’ The eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were periods of great upheaval, including growing religious debate, recurrent cycles of war and famine, and the growth of working-class political movements. By inculcating these middle-class values of industriousness and piety in the children of the poor, the governors felt that they were saving these individual children from a life of sin and distress, but also contributing to the security of the nation by producing obedient workers who would not fall into criminality or question authority.

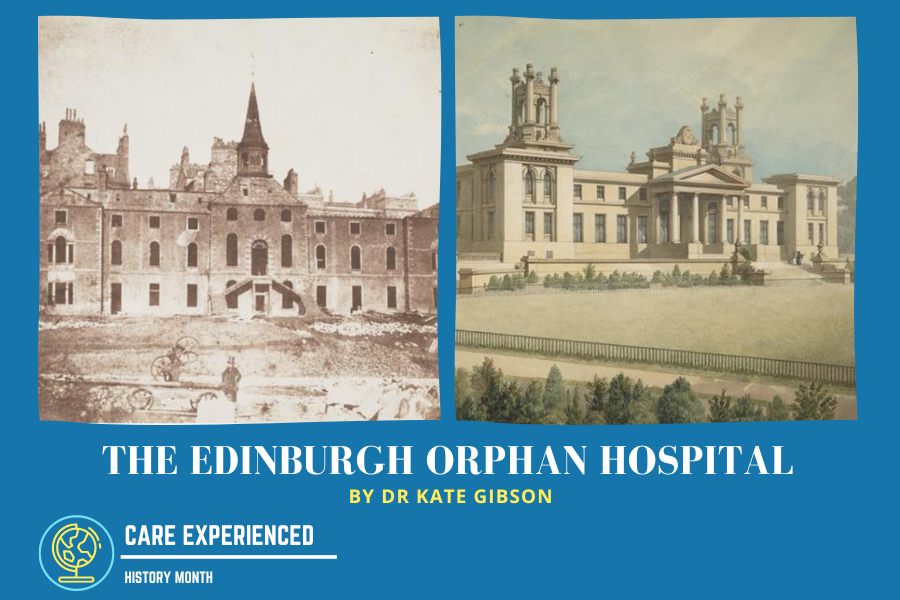

By 1734, the original building in Bailie Fyfe’s Close was deemed too small, and the governors raised a subscription to pay for a new, purpose-built Hospital nearby, at the junction of Princes Street, under the present Waverley Station. At this time the New Town had not yet been built, so ‘the whole space to the west and north was a free and unbroken line of fields’. The building slowly grew, with new east and west wings added, a spire, wash house, laundry, schoolroom and infirmary. The governors built a chapel in the grounds for the children to attend on Sundays and where they could hold annual sermons by guest preachers to raise money for the Hospital. By the early nineteenth century, though, the governors became worried about the health effects of the urban expansion of Edinburgh. The Hospital was now surrounded by smelly and polluting industries such as a farrier forge, tar boilers and a slaughterhouse. ‘That which had originally been a clear, detached, and airy situation, as the site of every such Institution ought to be, became, comparatively, a close and confined spot… surrounded almost on all sides by lofty buildings, with the drains from the New Town passing under the very walls of the house.’

The governors had always taken the health of the children seriously. The Hospital had a dedicated surgeon, and any child showing health problems was sent to recuperate at a house in Leith ‘to which the children of feeble constitutions were removed for the advantage of the better air’. By the late eighteenth century, the children had lessons in gymnastics, and ‘regular seabathing’. Concerns about the Hospital’s location, though, motivated the governors to commission a report on the mortality rate of children in the Hospital, which recommended a move.

In 1828, they bought some land in a then very rural hilltop location above Dean Village, and invited fashionable architect Thomas Hamilton to design a building which could combine comfort and health with beauty. The new building was intended to demonstrate the enlightened and modern attitudes of Scottish philanthropy. It had separate spaces for boys and girls, a dedicated room for the sick, ‘secluded from noise by the intervention of double doors, thick walls, and distinct passages’, running water, heating, and gas lights in every room. The building as it exists now – the ‘Modern Two’ art gallery – is imposing and palatial, and this architecture was deliberate. The governors did not want it to look like an Orphan Hospital, avoiding ‘a building at all resembling an ordinary workhouse or penitentiary, or any thing even that was mean in its appearance, or out of keeping with its proximity to the metropolis… or in violation of the improved taste of the times’. Acknowledging that some people might find it ‘too showy and ambitious’, they argued that such a beautiful building would actually improve the lives of the children living in it – its ‘cheerfulness of aspect’, they hoped, would ‘exercise a certain moral influence… which tends to impart to the individuals that inhabit it’. The building cost over £12,000 (nearly a million pounds today) and was intended to be at the cutting edge of philanthropic design. The building was in use as an orphans’ home until the 1990s, and today the organisation still exists as the Dean & Cauvin Young People’s Trust.

Today, it is hard to believe that it was not always intended to be an art gallery. Its long corridors and interlocking rooms seem ideal for displaying art, unless you know the history of the hundreds of children who passed through its doors over the decades. Physical places can provide a tangible, emotional connection with the past, so next time you visit, or pass through Waverley station, spare a thought for the history contained in its walls.

Sources

· The archive of the Orphan Hospital, National Records of Scotland: GD417

· An Historical Account of the Orphan Hospital of Edinburgh (Edinburgh, 1833)