Content warning: abuse

According to the the Child Migrants Trust, Britain is the only country to have used child migration as a consistent part of its child care policy over several centuries.

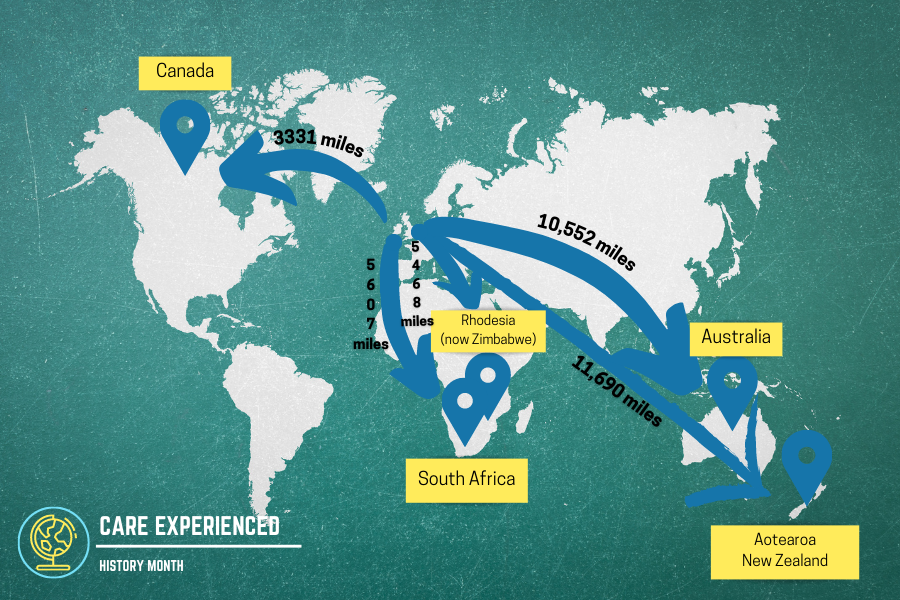

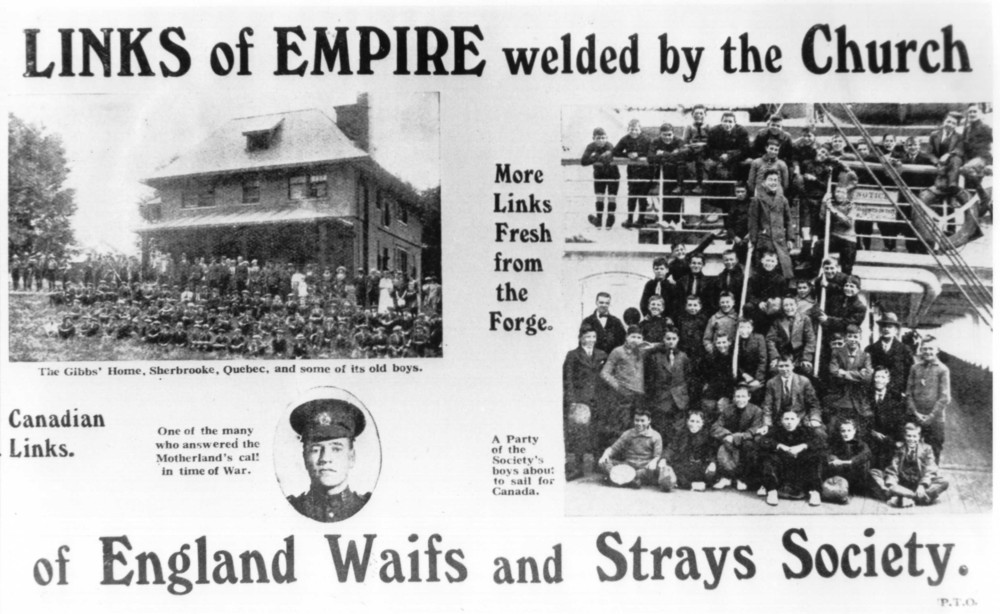

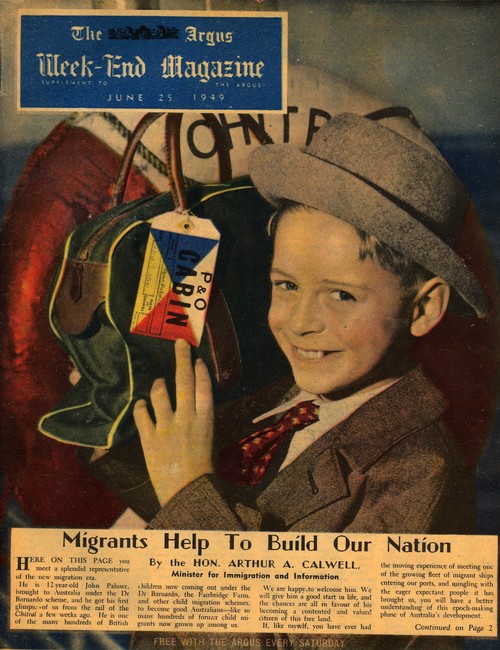

Overall, it is estimated that, in different waves, 150,000 British children, principally in state care, were sent from the UK to other countries. While the earliest child migration from the UK took place in the early 17th century to Virginia (part of the USA)(Wagner, 1982) the majority of British children were sent unaccompanied to the ‘new Dominions’ between the 1870s and the mid-1930s. In this period they were were sent to countries with which had been colonised as part of the British Empire: Australia, Canada, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), New Zealand and South Africa. This wave of child emigration was explicitly linked to securing the continuation of white British governance and empire in those countries, and took place with a good deal of fanfare and positive publicity within Britain itself.

Questions can be asked as to several aspects of this policy before 1945 – for example there was evidence of the abusive treatment towards child migrants in Canada in the late 19th Century, which led to a temporary cessation of that scheme (Magnusson, 2006; National Archives, 2009). However, the greatest scandal involved the use of child migration from the UK in the period from 1945- 1970. This was principally to Australia but also to Canada, New Zealand , Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). It is in respect of this wave of child migration that this piece focuses. Though smaller numbers of children were involved in this wave of child migration, the numbers are still very considerable – around 10,000 children were sent to Australia alone (Humphreys, 1994), while 549 were sent to New Zealand and 276 to Rhodesia. The controversy concerns the manner in which this last wave of child migration was allowed to happen without due scrutiny and oversight from relevant authorities in either Britain or the countries to which children were sent; the lack of meaningful consent from children and many of their birth families to the migration; and the appalling treatment, and abuse, many child migrants encountered in the countries to which they were sent. Most child migrants in this period were sent by voluntary societies in Britain who were responsible for running residential child care homes and were between seven and ten (Bean and Melville, 1989), though some were as young as three.

Overview of the Scandal of Child Migration after 1945

Referring to the post-1945 child migration scheme, Bean and Melville comment that the ’history of child migration in Australia is in many ways a history of cruelty, lies and deceit’ (Bean & Melville, 1989, p.111). Children were informed that parents were dead when this was not the case, family members were not informed children were being sent abroad or misinformed about the nature of the scheme, family members’ objections to a child being sent were overridden, contact between the children and family members in Britain was discouraged, with letters censored and sometimes withheld, and siblings sent to Australia together were frequently separated on arrival (Bean & Melville 1989). In some cases young children had their names changed so that their birth families could not find them.

Children were frequently misled by the staff looking after them both about what emigration entailed, as well as their family circumstances, in order to encourage their agreement to leave. One man sent to Australia from Nazareth House (a residential children’s home in Lasswade, Scotland), in 1951 commented:

“The nuns told us we were orphans, that we had no family and no future in Scotland. They told us Australia was the Promised Land where we could ride to school on ponies.”

(quoted in Abrams, 1998, p.143).

However despite these promises, migrant children overwhelmingly swapped institutional care in Britain for institutional care in their country of destination with fewer safeguards for their welfare (Gill, 1987). Despite the public statements that child emigration schemes were for orphaned children for whom there were no chance of a family placement in Britain, most children had at least one living parent (Bean& Melville 1989). The abuse experienced by some of those sent abroad in this period was marked. This included a range of physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as care that consistently failed to meet the children’s core needs (Humphreys, 1994).

How Did the Child Migration Scheme Restart after 1945?

Within the UK, there were concerns over child migration schemes from the start of the post-war period. Whereas the earlier waves of child migration had heavily and positively publicised within the UK, those in the post-war period were undertaken rather quietly (Abrams, 1998).

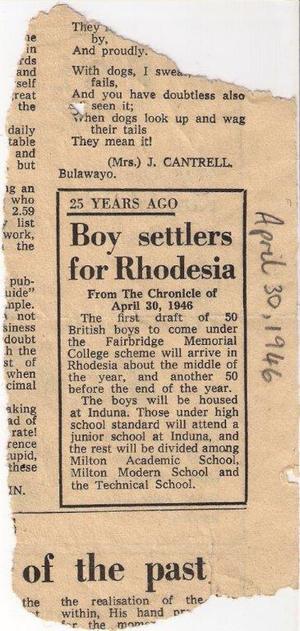

Immediately after World War II, British Columbia (in Canada) lifted child migration laws temporarily from 1945 – 8, and Fairbridge Farm School sent children from England to training centres for these three years (Magnusson, 2006). The renewal of the Empire Settlement Acts and the assisted passage agreement with Australia in 1946 facilitated emigration there, as well as making emigration possible to New Zealand, Rhodesia and South Africa (Bean & Melville, 1989). In Australia, where most child migrants were sent, the need to rebuild after World War II, combined with a fear of surrounding Asian countries and historical links to the British empire, led to a view of child migration as a way of increasing those of “good white British stock”, within the country, thereby securing its future.

The concerns over child migration in the immediate post-WWII period meant that the UK 1948 Children Act contained specific provisions regarding child migration, however these were less stringent that they might have been. Amongst the proposed safeguards were that the Home Secretary had to approve the emigration of each individual child, and be persuaded it was in their best interests; that the parents of the child should be consulted and, where this were not possible, the child themselves had to give clear consent.

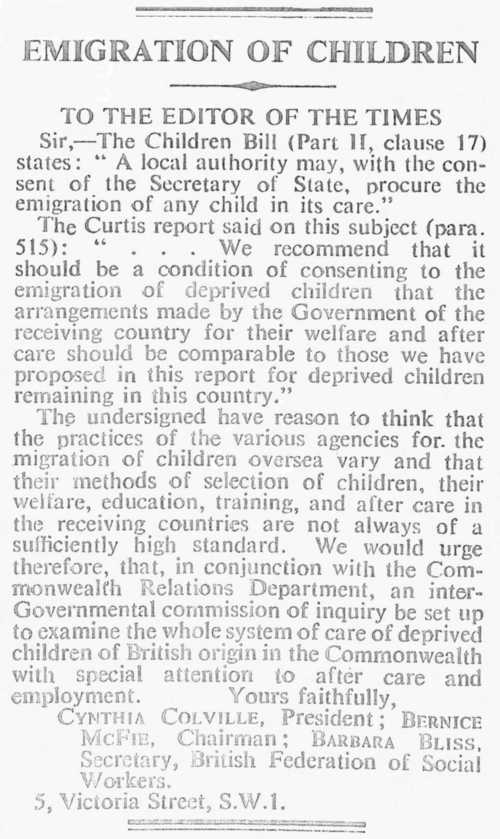

The British Federation of Social Workers had voiced concerns about child migration at this time. This was after the Federation had been informed that children recruited by the Fairbridge Society to go to South Rhodesia were not actually orphans, as claimed. The Federation also expressed concern over what it had heard about the enforced censorship of letters sent between children and their families, and the fact children were encouraged to terminate contact with family members (Bean & Melville, 1989). The Federation was assured by the Fairbridge Farm Schools of Australia and Canada that there would not be any large-scale migration of children. The Federation nonetheless lobbied during the passage of the Children’s Bill (what would become the Children Act 1948) for specific regulation of the activities of voluntary societies involved in emigration schemes. Section 33 of the Children’s Act 1948 stated the Secretary of State ‘may by regulations’ control emigration arrangements for children cared for by voluntary organisations. The Federation wanted ‘may by regulations’ to be replaced by ‘shall by regulations’ (Bean & Melville, 1989). Crucially, though, it withdrew its insistence after assurances issued by the Lord Chancellor, Viscount Jowitt, during the Parliamentary debate on the bill . Jowitt gave assurances that the Home office would ensure no child would be sent abroad ‘unless there is absolute satisfaction that proper arrangements have been made for the care and upbringing of each child’ (cited in Bean & Melville, 1989, p.169).

This assurance proved completely hollow. The priority given to the scrutinising the welfare of child migrants sent to Australia is suggested by the fact that the first formal government assessment of child migrants’ conditions was not undertaken until 1956. Notably though, the assessment was highly critical of the care provided to child migrants. The report also detailed criticisms about the care provided by a number of residential institutions for child migrants, however, these criticisms were contained within a part of the report which was not published. And, despite the report, the numbers of children sent to Australia from 1956- 66 increased (Bean & Melville, 1989). It was not until 1982, well over a decade after the final child migration had ended, that the British Government made it a legal requirement for any voluntary association to get the consent of the Secretary of State before sending a child abroad (Bean & Melville, 1989).

The Abuse and Poor Treatment of Child Migrants

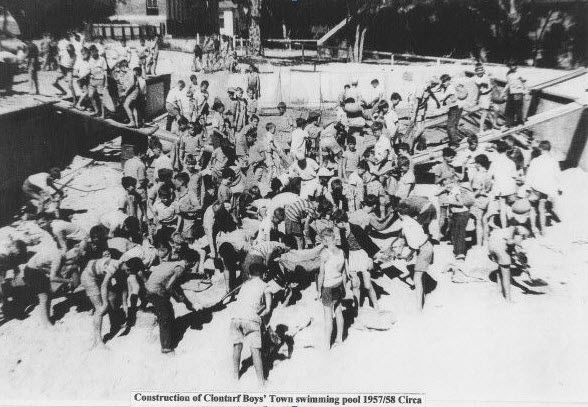

The lack of formal regulation of the institutions that child migrants were sent to meant there was huge variation in care according to the individual carers and individual institution. While there were undoubtedly carers who were not abusive, all the institutional care provided to Australian child migrants was harsh in the sense of being disciplinarian. Over and above that, there was also stark, shocking and marked child abuse. Those child migrants subject to the worst abuse were Roman Catholic boys sent to the Christian Brothers’ remote farm schools in Bindoon, Tardun and Clontarf, Western Australia where there was systematic and widespread physical, emotional and sexual abuse (Bean & Melville, 1989). Children as young as eight were forced to engage in construction work at Bindoon (Humphreys, 1994) while the abuse of children at those schools was sometimes so severe that at least half a dozen boys had to have corrective surgery; none of the cases were reported as matters of concern by the medical staff involved (Bean & Melville, 1989). Former residents of Goodwood Orphanage for girls described treatment from staff characterised by physical cruelty, a lack of emotional warmth and an uncaring regime that in which the girls were prevented from keeping any personal possessions and had to share items such as toothbrushes and underclothes (Bean & Melville, 1989).

The regimes at Fairbridge Farm schools in Pinjarra, Western Australia, and Molong, New South Wales were generally better but a child’s experiences were highly dependent on the cottage parent in charge in a particular cottage (Bean & Melville, 1989). The Australian Senate Inquiry (2001) found that child migrants were subject to a range of sexual, physical and psychological abuse. Children were beaten with specially made implements designed to cause as much pain as possible and the severity of some beatings caused physical impairment in later life. While some physical chastisement administered would have been considered legal at that period: ‘Brutality was endemic at some institutions and at times descended into what can only be described as torture’(Australian Senate Inquiry, 2001, p.72). The Inquiry found that child migrants were exposed to sexual abuse from a range of individuals including priests, other workers and regular visitors to the institutions, members of families to whom children were sent on holidays or to work for and, also in some instances, other older children in the same institutions (Australian Senate Inquiry, 2001).

In addition to such shocking direct abuse, the treatment and care of children was often notably poor. The provision of basic items such as food and clothing was often inadequate, educational provision was poor and children were sometimes re-named, or referred to by a number rather than name, and generally deprived of any understanding of their cultural and family history (Australian Senate Inquiry, 2001). On leaving the residential institutions, these young people who had been encouraged to break any contact they may have had with family members in Britain, were very rarely provided with any type of after-care to help them make the transition into wider Australian society, of which they had little knowledge, and with which they had no direct ties (Australian Senate Inquiry, 2001).

How the Post-War Child Migrant Scheme Came to Light

While there was sporadic mentions of the child migrant scheme in local press coverage (see Archive Press cuttings) there was little awareness of it beyond individual cases, or of the scale or nature of it within either the UK or Australia, Canada, New Zealand or Rhodesia. In 1986 Margaret Humphreys was working as a social worker working for Nottinghamshire County Council, in England. In this capacity in 1986 she was contacted by an adult child migrant living in Australia, who was looking for her birth certificate as she was getting married and needed it for that purpose. The woman believed she had been orphaned and sent from the UK to Australia as young child (Humphreys, 1994). Humphreys was unsure of the account at first, but started to investigate. In doing so she started to discover the realities of the child migrant scheme, visiting Australia to find out more. National attention was brought to the matter by a national UK newspaper working with Humphreys to expose the issue. Initially funded by her Local Authority, she set up the Child Migrants Trust to support child migrants and help reunite them with their families where possible. Phillip Bean (a Child Migrants Trust trustee) and Joy Melville’s 1989 book , Lost Children of the Empire, and an accompanying documentary of the same year, helped bring further attention to the issue in the UK. A TV film, The Leaving of Liverpool, was screened on BBC 1 one of the main TV channels in the UK in 1993 massively increased exposure of the issue. Helplines staffed by Child Migrants Trust staff received 10,000 calls. Further exposure was gained by the publication of Humphreys’ own book Empty Cradles, in 1994, which sold over 75,000 copies. The 2010 film Oranges and Sunshine, directed by Jim Loach, portrays the post-war child migrant scheme, and Humphreys’ role in exposing it. As noted below, Australian child migrants, who were by now adults, were also seeking recognition from the Australian authorities of what had happened to them. Amongst them was David Hill (see below) who campaigned for the Australian Government to recognise the poor child migrants to Australia, and who wrote his own book about the Fairbridge Farm School to which he was sent.

Government Acknowledgement and Inquiries

An Australian senate inquiry into the child migrant scheme to Australia in 2001 was followed, in 2009, by an Australian Government apology to all child migrants for their treatment. This was followed in 2010 by the UK Government , when Gordon Brown issued a formal apology. Brown’s speech, addressed to an audience of former child migrants, referred to the post-war child migrant scheme as ‘an ugly stain on our country’ and stated to tjem that it had involved ‘not just transportation but deportation from your home countries’. A Canadian Parliamentary Apology was offered in 2017. While these are welcome it should be noted that governmental recognition of the harms done to child migrants and their families has been slow, and has come only after years of hard campaigning by former child migrants themselves and organisations supporting them, like the Child Migrants Trust.

This is illustrated by the UK Government’s 1998 Department of Health Memorandum which set out the Government’s position at that time – a time when the evidence of many of the injustices within the child migrant scheme, as well as much of the abuse, had already become clear. The memorandum stated that the Government’s position was that:

Child migration as a policy was, in a social climate very different from that of today, a well-intended response to the needs of deprived children. At the time this was seen to be in the best interests of the children concerned, providing them with a fresh start in countries which potentially offered them greater opportunities. There were many success stories.

The defensive tone struck here seems to deny the possibility that what happened to child migrants was known to be mistaken and wrong at the time. It is accurate to say, as the memorandum does, that the post-war child migration scheme was legal and took place in a different social climate. It is also easy to misjudge actions undertaken in previous time periods by the values of the present day. What the memorandum overlooks, however, is that the oversight and safeguards which were promised during Parliamentary passing of the 1948 Children Act, in response to the concerns raised about the continuation of the child migrant scheme, were never put into place, as had been pledged. It also overlooks the way in which the child migrant scheme operated in a clandestine way, that children and their families were lied to and, most of all, the widespread abuse that a number of child migrants were subject to. That such abuse occurred to such a degree can only be properly understood by looking beyond individual abusive carers to the systemic failings of the child migrant scheme and by recognising the failure to meet the moral responsibilities which both government and voluntary sector agencies in all countries had for ensuring the safety, and promoting the welfare of, children in state care.

Former Child Migrants Today

While the focus within the child migrants scheme has been understandably been the deception of children and families, the loss of identity and connection and the horrendous abuse experienced by many, it is notable that there were also ‘success stories’. Sometimes such success stories co-exist with difficult personal histories in that some former child migrants experienced both formal ‘success’ in terms of achieving prosperity and careers in their adopted countries, but also carried the psychological, emotional and sometimes physical scars of enforced separation from their birth families as well as the abusive treatment to which they were subject. The Museums Victoria, Australia, carried an exhibition on Child Migrants between 2011 – 12 and developed a companion exhibition, Stolen Childhoods, to tell the story of three child migrants in Victoria and Tasmania: Hugh McGowan, Sandra Anker and Michael Harvey: https://museumsvictoria.com.au/article/stolen-childhoods/

The Child Migrant Trust continue to do work to support former child migrants and to re-establish contact between them and their birth families where possible.

It is also worth noting that the motives behind the child migration schemes in the post-war period varied according to the country of destination. The Fairbridge scheme to Rhodesia sent children out to become part of the governing white British elite, and was a success in those terms. Those children sent out to Australia, on the other hand, were earmarked to fill shortages of manual workers in the labour market. As a result of these differential motives for the schemes, the treatment and integration of those children sent to Rhodesia was very much better than that of children sent to Australia (Bean and Melville, 1989). Children sent to New Zealand tended to fare better than those sent to Australia in that they were sent to foster homes, rather than to institutions or to farms as labourers, but a lack of proper oversight was also common.

Prominent former child migrants include Andrew Murray who was sent a child migrant to Rhodesia in 1951, before going on to study as a Rhodes scholar at the University of Oxford, and the becoming a successful businessman and Senator for the Australian Democrats from 1996 – 2008. David Hill was a child migrant to Australia. Having been in a Barnardo’s home he migrated to to Australia with his brothers, aged 12, in 1959, aboard the SS Strathaird. His mother arrived in Australia a few years later. Having worked in a number of jobs, Hill become a prominent director of public and private sector organisations. He has spoken of the harsh treatment he experience in institutional care in both England and Australia. He also been a campaigner for the recognition of the poor treatment of child migrants to Australia by the Australian and British governments, writing a 2007 book about this: The Forgotten Children: Fairbridge Farm School and Its Betrayal of Britain’s Child Migrants to Australia.

Why Did the Post-War Child Migrants Scheme Happen?

This pieces finishes by trying to understand how such a bleak episode in the all of the named countries’ history could take place in a relatively recent time period. While awareness of child sexual abuse was not widespread until the 1980s, there was certainly knowledge of the possibility of the sexual abuse of children, the need to promote children’s welfare and an awareness of the possibility of physical abuse and poor quality care in the period of the post-war child migrant scheme (Sen et al., 2007).

One of the premises for child emigration in the post-war period was on child welfare grounds: it was argued that it would be difficult to find the children foster families in Britain (Abrams, 1998). It is possible that some professionals and organisations genuinely believed that child migration provided a good opportunity for the children sent, as well as supporting the development of those countries to which they were sent. If that were the case, however, they were grossly negligent in finding out how the scheme was actually operating, and in following up how the children sent from the UK were faring in their new countries.

Hendrick (2003) points towards other far less altruistic motives behind the child migration schemes take as a whole, beyond the post-WWII wave. Firstly, he argues, there was an economic interest as it was cheaper for organisations to maintain children in the Dominions than in Britain. Secondly, there were political concerns about the numbers of homeless children in cities and how this could affect social order. Thirdly, religious concern within the ‘child rescue’ movement that children cared for in institutions had to be removed from what was considered the damaging influence of birth family members, whose lifestyles were viewed as corrupting and immoral. Finally, imperialism provided a motivation as, from the beginning of the 20th century, child emigrants were seen as a means of solidifying British control of its overseas imperial territories.

As a social worker who worked children and young people in care system in a far more recent period, a few things stand out about the scheme and why it may have happened. Firstly, the children and young people came from poorer families, who were relatively disempowered, and who could be marginalised more easily by those agencies involved in the child migrant scheme. The children and young people themselves were separated from their families and were therefore largely reliant on the good care of those in UK institutions protecting their interests – in a period before child complaint and a children’s rights agenda had emerged at all. They failed to do so.

This failure though was not totally by chance. The child migrant scheme suggests the regulatory system was entirely inadequate at that time. Current systems of checks and balance for children and young people in care can appear bureaucratic and burdensome. Getting the balance between the imposition of bureaucratic checks and scrutiny, and supporting children and young people in care to get on with the living of their lives is very important. But, it is also crucial to remember that the effective operation of a regulatory system can prevent abuses, such as those inherent within the child migrant scheme. As noted, the 1948 Act almost contained the stipulation that the Home Secretary should have to approve the migration of each child sent abroad. Not only should this have provided a clearer safeguard, it would have provided a line of accountability and responsibiity within the heart of the UK Government, which could have focused successive governments’ attention on exploring the lived realities of the child migrant scheme far more closely. The fact that during the passage of the 1948 Act the obligation on the Secretary of State was changed from a duty to a discretionary power (for ‘shall’ to ‘may’) appears to have been critical. Grier (2002) argues that there was an intentionality to successive British Governments’ failure to regulate the actions of voluntary agencies involved in child migration. On the one hand, the lack of direct state involvement in child migration schemes – in most cases – distanced government from responsibility for those children. On the other, successive governments’ acceptance of child migration – particularly to Australia – allowed them to support those countries to attract immigrants of ‘good British stock’ to support the infrastructure of those countries, and thereby avoid diplomatic fallout.

Finally, in terms of social work practice, social workers can certainly look positively on the role of the British Federation of Social Workers in 1948 in challenging elements of the child migration scheme at that time, but they must also recognise that the Federation failed in their attempts to get proper scrutiny of child migration into the 1948 Act, and then also failed to effectively scrutinise what happened after the 1948 Act had been passed. The role of social worker Margaret Humphreys in recognising the issue of child migration, raising the profile of the child migrants scheme, and in tirelessly campaigning to help child migrants as part of the Child Migrants Trust has rightly been highly praised and recognised. But it must also be recognised that there were numerous other institutions and professionals, including social workers, who failed child migrants and their families during the last wave of the child migrants scheme. A commitment to avoiding similar travesties in the future requires proper recognition that such travesties can occur when institutions and professionals working with children in care are part of a system which lacks sufficient checks and oversight, and when individual professionals with knowledge of such travesties lack the significant professional bravery and integrity needed to call them out.

References

Abrams, L (1998) The Orphan Country. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers.

Australian Senate Community Affairs References Committee (2001). Lost innocents: Righting the record – Report on child migration. Accessed at: http://www.aph.gov.au/senate/committee/clac_ctte/ completed_ inquiries/1999-02/child_migrat/report/index.htm

Bean P. and Melville J. (1989). Lost Children of the Empire. London: Unwin Hyman.

Gill, A. (1998). Orphans of the empire: The shocking story of child migration to Australia. Sydney: Random House.

Grier, J. (2002). Voluntary rights and statutory wrongs: The case of child migration, 1948-67. History of Education, 31(3), 263-280.

Hendrick, H. (2003). Child welfare: Historical dimensions, contemporary debate. Bristol : Policy Press.

Humphreys, M. (1994). Empty cradles. London: Transworld.

Magnusson, A. (2006). The Quarriers story : A history of the Quarriers. Edinburgh: Birlin.

Sen, R., Kendrick, A., Milligan, I. & Hawthorn, M. (2007) ‘Abuse in residential child care: A literature review’ in Shaw, T. (ed.), Historical abuse systemic review: Residential schools and children’s homes in Scotland 1950 to 1995. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2007/11/20104729/20

Wagner, G.(1982) Children of the Empire, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson.