cw: abuse, sex work, sexual assault.

The scandal of the Magdalene Laundries in Ireland has made headlines because of the extent of the abuse experienced by the girls and women committed to the laundries, where many spent their lives and died in these institutions. Survivors and campaigners have highlighted this abuse, and their experience has been portrayed in documentaries and films. The Magdalene laundries were used for punishment and imprisonment, and the erasure of the women’s identity.[i]

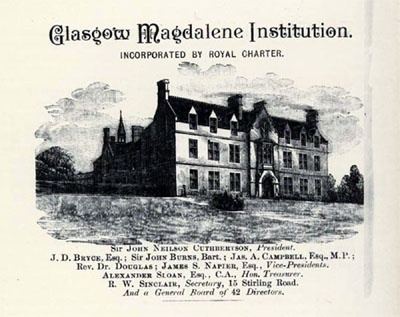

Magdalene asylums, however, were not just an Irish phenomenon. The institutionalisation of prostitutes and ‘fallen women’ started in medieval Europe, and the first such institution in the UK opened in England in 1758 – the Magdalen Hospital for the Reception of Penitent Prostitutes. In Scotland, the Edinburgh Royal Magdalene Asylum opened in 1797. Following the Edinburgh Magdalene Asylum, more rescue homes opened across Scotland throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the major Scottish cities had a number of them. These institutions went by a range of names such as ‘rescue home’, ‘female shelter’, ‘reformatory’, ‘home of mercy’ as well as Magdalene asylum.[ii]

The drive behind the opening of these rescue homes and Magdalene asylums was a shift from the punishment of prostitutes to ideas of reform and rehabilitation. Social reformers focused on ways to save ‘repentant girls and women’ and to support them to take up a useful place in society. Rescue homes and Magdalene asylums became central to this mission.

The focus of the reformers, however, was not just prostitution but broader concerns about the moral behaviour of girls and young women and this was based on class and prejudice. Rough language, drinking and swearing by women in public were linked with sexual promiscuity and hence with prostitution. This meant that any girl or young woman, whose sexual or moral behaviour was questionable, could find themselves in a rescue home or asylum. Even the victims of sexual assault were considered ‘tainted’ by their experience and were in need of moral rehabilitation.[iii]

Girls as young as eight could be placed in these institutions. The girls might be an orphan or could have been deserted by their parents. Others were recruited to the homes due to vagrancy, juvenile delinquency, sexual misbehaviour or being found in brothels or in the company of prostitutes. Records show that some of the girls were reunited with their parents following their time in the asylums, while others were placed as domestic servants. Some were supported to emigrate to the colonies.

Scotland’s Magdalene asylums and rescue homes varied widely in terms of their organisation, management, methods and focus. Many were established as charitable institutions run by lay committees, while others were set up by religious organisations such as the Church of Scotland, Salvation Army or Catholic religious orders. All, however, were based on wholesome, Christian discipline which underlined the repentant’s goal of rehabilitation. Although placement in the refuge homes and asylums was voluntary and many women applied for admission, the homes were part of a wider network of residential establishments such as prisons, reformatories, industrial schools, orphanages and the poorhouse, and so there could often be an element of compulsion in how girls and young women entered these institutions.[iv]

The rescue and reform of these girls and women, then, was based on three elements of education and discipline. They would be saved through Christian worship, prayers and religious instruction. They would be trained to be obedient, respectful and hard-working employees, able to take up a productive role in society. They would also be taught the necessary skills regarded as suitable for their status: domestic duties such as cleaning, sewing, cooking and laundry. In many of the refuges, the focus on laundry work increased dramatically over time, as this became an important source of income for the institutions.

There were high standards expected of the girls and women, with strict rules and discipline. Punishments for poor behaviour and indiscipline could include solitary confinement, hard physical labour, or women could be expelled from the home. Even though placement was voluntary, it could be very difficult for the girls and women to leave. The homes had policies that girls and women could only leave when they had demonstrated their rehabilitation or they could impose a minimum length of residence of up to two years. Those who wished to leave early might be placed in solitary confinement to consider their decision and would be scolded and reprimanded.[v]

Another institution closely associated to the Magdalene asylums were the Lock Hospitals and lock wards for the treatment of female venereal disease patients. Throughout history, venereal diseases (sexually transmitted infections) have been linked with prostitution or immoral sexual behaviour, and the patients were generally considered as prostitutes. Girls as young as seven were treated in the Lock Hospital. Before the use of antibiotics, painful and toxic treatments such as mercury baths were the only therapy, despite the evidence of the damage they could cause.[vi] The Lock Hospital provided the medical treatment and then the Magdalene asylum provided the reformatory role. They depended on each other.[vii]

Into the 20th century, the routines of religious instruction, education and hard work continued in Scottish rescue homes and Magdalene asylums. Domestic work and the laundry remained the main form of work and training. Despite criticism of their harsh regimes, the tedious work schedule, and the lack of focus on the individual needs of the girls and women, there was little change in some of the homes, even into the 1950s. [viii]

This was highlighted by the situation behind the closure of the last Magdalene institution in Scotland, Lochburn Home in Glasgow. Girls were placed in Lochburn Home as juvenile offenders or because they were in ‘moral danger’ by probation officers or by their parents. Newspaper reports at the time told of mass breakouts from the home as girls escaped by climbing over the walls on a number of different occasions. There were also allegations of ill-treatment, beatings, dousing with cold water and cold baths. The Lochburn Home was closed shortly after this.[ix]

The Magdalen asylums and rescues homes operated for over 150 years and this brief account only touches on the experience of girls and young women over that time. These institutions focused on the stigmatisation of girls and young women because of their perceived transgressions against the middle-class sexual norms of the time. Their misdemeanours, their guilt, their shame, and their attempts to improve their lives, led to a harsh time in these institutions with strict rules and discipline, and long days of hard labour.

References:

[i] Louise Brangan (2024) States of Denial: Magdalene Laundries in Twentieth-Century Ireland, Punishment & Society, 26(2), 394-413.

Katherine O’Donnell, Maeve O’Rourke and James M. Smith (2022) Redress: Ireland’s Institutions and Transitional Justice. Dublin: University College Dublin Press.

[ii] Jowita Thor (2019) Religious and industrial education in the nineteenth-century Magdalene asylums in Scotland, Studies in Church History, 55, 347-362.

Linda Mahood (1995) Policing Gender, Class and Family: Britain, 1850-1940. London: UCL Press.

[iii] Linda Mahood (1990) The Magdalenes: Prostitution in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge.

[iv] Jowita Thor, Religious and industrial education.

[v] Linda Mahood, The Magdalenes.

[vi] Andrew Kendrick (2023) Caring for children with infectious diseases: Children’s experiences of fever hospitals and sanatoria in Scotland, The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 16(1), 9-27.

[vii] Linda Mahood, The Magdalenes.

[viii] Louise Settle (2016) Sex for Sale in Scotland: Prostitution in Edinburgh and Glasgow, 1900-1939. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Louise Jackson and Angela Bartie (2014) Policing Youth: Britain 1945-70. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

[ix] Linda Mahood, The Magdalenes.