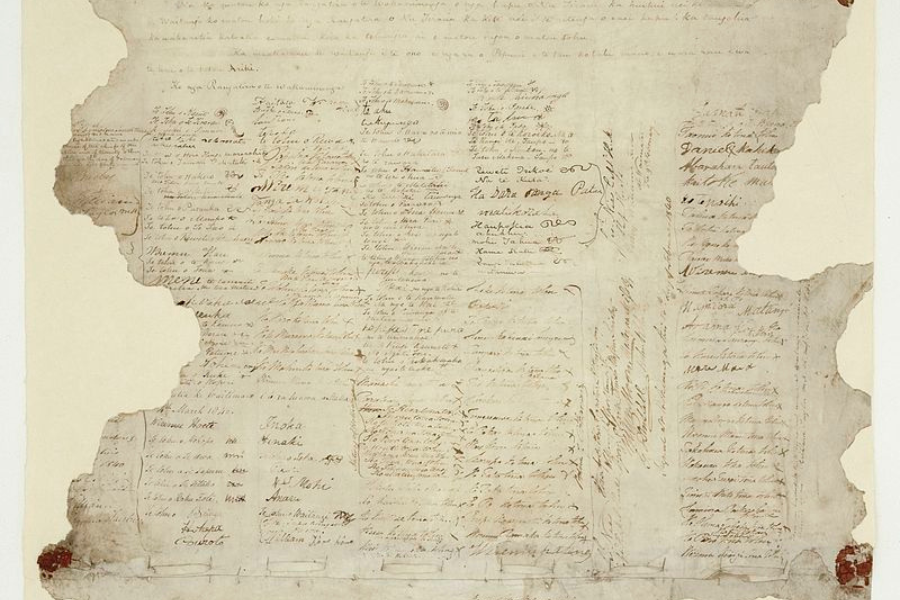

Aotearoa New Zealand is finally beginning to acknowledge that for generations there has been a constant failure to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the treaty of Waitangi). Te Tiriti o Waitangi binds New Zealanders as a nation and promises Maori the right to Tino Rangatiratanga (the right to determine, define and decide how we as Māori live and take care of ourselves -Moana Jackson).

As a nation, New Zealand has a lot of work to do when it comes to honouring the words of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which is reflected in The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care’s Interim Report ‘Tāwharautia: Pūrongo o te Wā’ key findings: up to 655,000 children, young people and vulnerable adults were in State and faith-based care during 1950-2019 and up to 250,000 of these children, young people and vulnerable adults were abused.

Throughout New Zealand’s history, Care Experienced young people have been without a voice in an oppressive, abusive and racist state care system. It has long failed to respect the role that young people and their whānau (families), hāpu and iwi (tribes) have to play in their own lives.

Despite many reviews of the state care, protection, and youth justice systems over the years in Aotearoa New Zealand, the state has only recently included the voice of those with care experience in the decision-making process.

The voice of experience is imperative to create effective change in these systems because those with lived experience understand more than anyone else the impact of childhood without adequate care and protection.

Care Experienced History Month welcomes you to join us on this journey of reflection, learning and remembrance. Which will honour those who have gone before and their experiences.

Whether you work in the sector or not, as people we all have something to learn from the history of those who have been through state care.

“Titiro whakamuri, kokiri whakamua” – look back and reflect so you can move forward. Given the purpose of this month, this whakatauki (proverb) is suitable, as we marked the first-ever Care Experienced History Month in 2021. We continue to recognise the month each year.

Take this opportunity, to stop and reflect on the experiences of those who have gone before us, to gain a deeper understanding of them, to hear and honour their stories. Let’s look back and reflect in order to move forward together.

Whāngai

Whāngai is a Māori customary practice where a child is raised by someone other than their birth parents – usually a relation. The practice is similar to both adoption and fostering, as a whāngai placement may be permanent or temporary. A parent who takes on a child as a whāngai is called a matua whāngai, while the child is known as a tamaiti whāngai.

There were a number of reasons that children were taken as whāngai, including:

finding homes for an orphaned child (pani)

taking a child from a large family that was struggling to support all the children

taking in a child who had young parents

taking in a child

finding a child for people who cannot have children

finding a child for older people whose children have grown up

strengthening whānau, hapū or iwi ties by strategically placing children within selected whānau.

particularly in the case of kaumātua (elders), taking in a mokopuna (grandchild) to pass down tribal traditions and knowledge

taking children in as whāngai so that they could inherit land.

Difference from adoption and fostering:

The whāngai system was open. It was done with the full knowledge of the whānau or hapū, and the child knew both their birth parents and whāngai parents. Rather than being the sole decision of the mother or parents, a wider community was involved in the decision.

Adoption and fostering are ways to find homes for children who are unwanted or whose parents have died, whereas in the case of whāngai, parents often gave up children to comply with the custom. Whāngai children were often wanted by both families. While whāngai has received some legal recognition at various times, it has largely operated outside the legal processes of adoption.

(Te Ara)