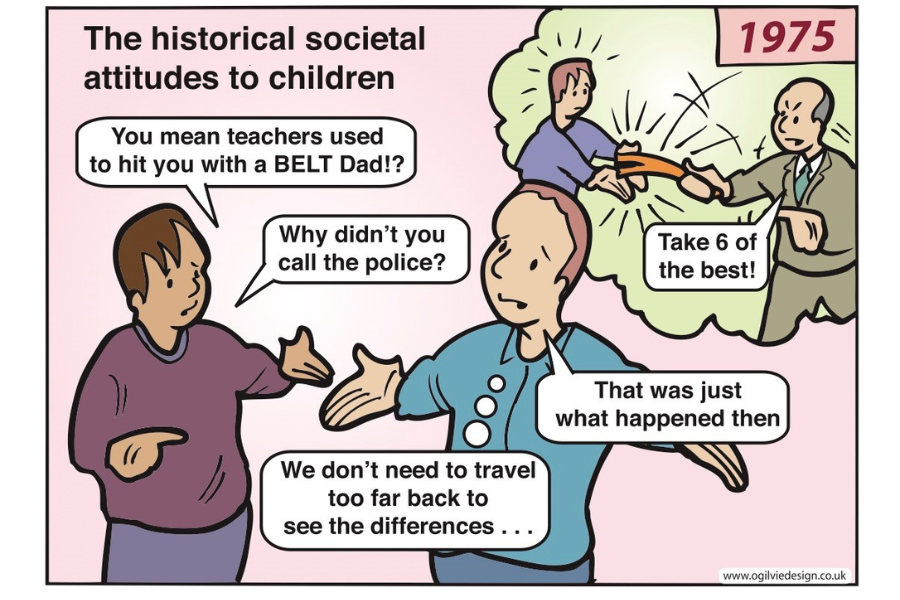

Back when I was at school in Alloa, I remember getting the belt for mucking about in Latin class. Yes, it was that long ago that we had to do Latin. I was lined up, along with quite a few other boys, for two strokes across the hand. That was the only time I had the belt. I gave up Latin and did a Higher in Technical Drawing instead. Getting the belt, or the tawse, was a standard punishment across schools and residential homes for many years in Scotland, and corporal punishment was accepted across Scottish society. Corporal punishment was banned in care settings and schools in the 1980s, but it was only in 2020 that Scotland banned corporal punishment by parents. In this blog, I will describe some of the history of corporal punishment for Care Experienced children and young people in Scotland over the years; including the way in which attitudes to corporal punishment meant that it could easily turn into abuse, leaving children hurt, terrified, humiliated and traumatised.

Before the 1800s, children had few legal rights and could suffer abuse and appalling conditions at home and at work. The common law gave some protection to children against cruelty and neglect. Parents and others such as teachers or carers could punish children, as long as it was ‘reasonable chastisement’, though there were few mechanisms to protect children. When the first law to prevent cruelty to children was passed in 1889, it did not affect the right of parents, teachers and others in charge of a child to administer punishment. This right to physically punish children remained in force through most of the twentieth century.

There were a number of concerns about corporal punishment over this period, and campaigns to ban the most extreme forms being used, such as flogging and birching. There was also an increasing recognition that corporal punishment did more harm than good. Most people, however, including social workers, residential workers, foster carers and teachers, thought that reasonable physical punishment was the right way to discipline children.

In the 1930s, regulations were drawn up for certain residential settings, such as approved schools and remand homes. These regulations set out in detail how corporal punishment should be carried out. Only a ‘light tawse’ should be used, and it was forbidden to use a cane or to strike a child. It should only be used rarely for girls, and then only a maximum of three strokes across the hands. Boys could receive strokes across the hands or ‘on the posterior over ordinary cloth trousers’. The number of strokes was different depending whether the boy was under 14 years old or over. These rules remained in force until a revised version of the regulations were cancelled in the 1980s.

In other residential settings such as orphanages and children’s homes, and in foster care, for much of this time there were no statutory regulations, or the regulations did not mention discipline and punishment. In some homes, staff received very little guidance about discipline and punishment, while in others, staff followed rules similar to those for approved schools. Corporal punishment was just an accepted part of life, smacking or belting was what happened if you did something wrong. Charles was in Aberlour Orphanage in the 1940s, and he recalls that, ‘We all got whacked if we done things wrong in the Orphanage but that was the accepted thing”[i].

Corporal punishment, however, could easily go beyond what could be considered ‘reasonable’ even by the standards of the time, when it was part of a harsh, rigid and cruel regime that showed little love or caring for children. In some foster and residential homes, punishment could be meted out for the smallest infringement, and could involve being hit with a belt, a cane, slippers, hair brushes, or being punched, slapped or hit on any part of the body. Children and young people were often punished for wetting the bed. This was seen as ‘dirty’ and there was no understanding that bed-wetting could be caused by stress and trauma, precisely the things that children and young people in care would be experiencing because of past suffering and being placed in care. The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry has shown how in some places, punishment was brutal and abusive in the extreme and these intolerable cultures lasted through into the 1980s.

During the 1970s, there were increasing calls to end the corporal punishment of children in schools and care settings, and by the early 1980s, a number of local authorities had banned the belt. In 1982, the European Court of Human Rights decided in the favour of two mothers who did not wish their children to receive corporal punishment in school, and in 1987, corporal punishment was banned in schools and in residential establishments. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child was signed in 1989. It explicitly protects children from, among other things, ‘all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse’ (Article 19), and states that no child shall be subject to ‘torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’ (Article 37). The Committee on the Rights of the Child has consistently called for the abolishment of corporal punishment.

In a recent article on discipline in the age of children’s rights, Joan Durrant and Ashley Stewart-Tufescu, set out five principles. Discipline should be non-violent. It should respect children’s evolving capacities, and it should respect the child’s individuality. Discipline should foster children’s participation and it should respect the child’s dignity.[ii]

In discussing corporal punishment, I have highlighted some of the worst excesses of the care system. We must not forget, however, the many positives that children and young people have experienced over the years. Increasingly, the rights of children and young people are becoming central to care services in Scotland; emphasising the importance of respect, relationships, participation, and individuality. And Scotland is one of the leading countries in the world in banning corporal punishment in the home and in all types of care setting.[iii]

References:

[i] Charles, cited in, David Divine (2013) Aberlour Narratives of Success. Durham: University of Durham

Department of Sociology & Social Policy.

[ii] Joan Durrant, Joan Ashley Stewart-Tufescu, A. (2017) What is “Discipline” in the Age of Children’s Rights?, International Journal of Children’s Rights, 25(2), 375.

[iii] Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children (2021) Prohibiting All Corporal Punishment of Children: Laying the Foundations for Non-Violent Childhoods. New York: Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children.